David Heilpern wrote a letter to the Land Transport Safety and Regulation department inquiring about the state of the current laws and in light of the research showing their ineffectiveness. The General Manager, Mr Andrew Mahon, answered this inquiry in a letter which we have attached below for reference.

The following is an open letter to Sussan Osmond, who Mr Andrew Mahon advised Drive Change to contact for further correspondence.

Dear Sussan Osmond,

I recently wrote to the Department of Transport and Main Roads expressing my concern over the ineffective and discriminatory drug laws in place for drivers. In this letter, I will address the Department of Transport and Main Roads directly.

What I presented to you was a concise report on how our drug driving laws are failing to improve safety as they discriminate against medicinal cannabis patients. While I appreciate your effort to offer a response, they were mostly evasive of the problem and prove that lawmakers aren’t relying on science or fact to formulate these laws. They are in need of an update.

In your response, you went as far as to agree they are “difficult to address” but failed to present any scientific evidence in support of the need to uphold the current jurisdiction. This proves a clear need for deeper understanding of the issue. I will provide that to you, and the wider community, here.

Cannabis as a drug

Cannabis is a drug that is proven to impair cognitive and motor function.

Mr. Andrew Mahon, Land Transport Safety and Regulation), QLD

In your letter, you address cannabis as a drug that is “proven to impair cognitive and motor function.” While this is true, it does not explain why the driving laws permit drivers to use other TGA-scheduled and over-the-counter drugs while operating vehicles.

This is the true crux of the issue between medicinal cannabis and roadside drug tests. The chemicals in pharmaceutical drugs can be detected with such tests. Conversely, cannabis can remain at detectable levels in these tests far beyond the time of impairment. This clearly points to current practices as the problem. Why are we still using outdated methods for roadside drug testing if we know without a shadow of a doubt that they’re unreliable?

That truth is that yes, cannabis is a drug. The wider truth of it is that there are plenty of drugs which get protection or a pass when they are detected in roadside tests. It is nothing short of discriminatory to deny such rights to medicinal cannabis patients, especially when you consider the effects on road toll.

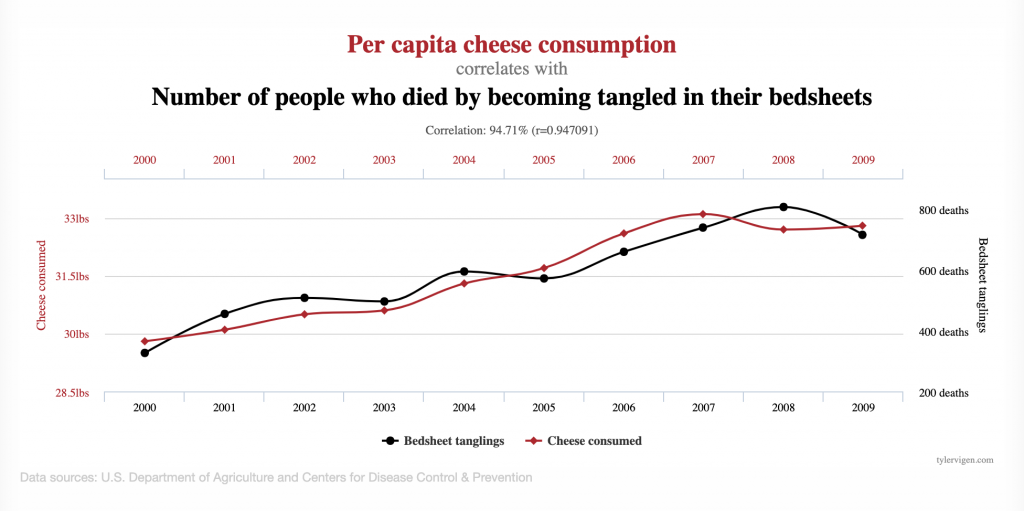

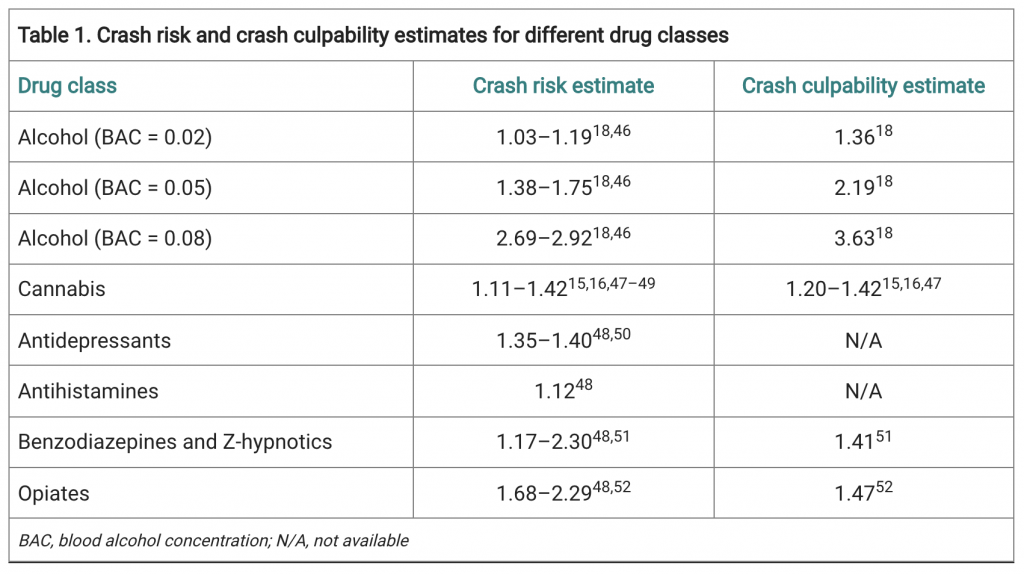

This has been an area that has been studied, and the results speak for themselves. The crash risk rate of drivers with a legal 0.05 BAC is 1.38-1.75. Once the BAC hits 0.08, this risk rises to 2.69. This is by far the highest crash risk rate of any of the other “impairing substances.”

Opioids are not far behind, presenting a crash risk of 2.29; Benzodiazepines carry a risk up to 2.30. Even antihistamines carry a crash risk of 1.17. So why then, if cannabis carries a crash risk of 1.11-1.42, is it the only of these drugs to be banned on the roads?

Discrimination, again, seems to be the only plausible answer.

These discriminatory laws seem to be rooted in an outdated and unreasonable vilification of cannabis, one that doctors and scientists are committed to re-educating the public on. In some capacity, the government is already on board, having approved medicinal cannabis for therapeutic purposes, and there are 75,000 patients in Australia with legal prescriptions.

While these medical professionals have done their due diligence, there has been no accountability from the Department of Transport and Mains Roads, nor the police, in understanding that cannabis as a legal drug holds value in public health.

Driving and Road Safety

The role of drugs, in varying forms, is a growing problem for road safety, not only in Queensland but nationwide and internationally

Mr. Andrew Mahon, Land Transport Safety and Regulation), QLD

The TGA has categorised some forms of medicinal cannabis as a Schedule 8 Controlled Drug. Also in this class are Oxycontin, Sativex, Amytil, etc. So, why is it that patients who test positive for these conventional medications are not committing a crime while medicinal cannabis patients are?

In your letter, you mention that “The role of drugs, in varying forms, is a growing problem for road safety, not only in Queensland but nationwide and internationally.” I absolutely agree with you on this point, which is why I am so adamant about adjusting the laws surrounding them.

The studies into road safety measures speak for themselves in this matter. After the introduction of seatbelts, there was a marked decline in road deaths. Likewise with airbags. In terms of roadside testing for cannabis, there has been no evidence that this decreases road toll. This points to the fact that we need newer methods of understanding what leads to crash risk.

A “zero-tolerance approach” to selected legal prescriptions is clearly not the answer.

You mention that we “take a zero-tolerance approach through presence based legislation as opposed to setting limits similar to alcohol,” but this argument is also untrue and shows the lack of research that’s been done on this topic. Tasmania has adopted laws protecting medicinal cannabis patients on the road. It proves that it is being done here in Australia and can be done throughout the entire country to defend medicinal cannabis users without a toll on road safety.

Yes, impairment increases risk of motor vehicle crashes–which is exactly what roadside drug tests should be looking for. You seem to understand this, saying that “impairments that will affect a person’s driving include their ability to anticipate hazards and unexpected situations, their decision making and their ability to respond quickly to changes in the traffic environment (e.g. reaction time).”

I ask again – why can other potentially impairing pharmaceutical medicines get a pass in roadside tests? Additionally, in testing for the presence of THC, which remains detectable past the point of impairment, it seems that there is no real evidence to back your claim that this is in the name of road safety when other harmful drugs are permissible and protected.

The bottom line on mouth swabs is that they do not work. If they did, we would not have seen a 55% increase in road crashes between 2012-2018.

I do agree with you on one point, that medicinal cannabis cannot easily be tested at the roadside. The legislation stops short of the true issue: what can we do that can make road safety a priority, without a discriminatory framework that infringes on public health?

New and Improved Methods

The answer is not as elusive as you state it to be. In actuality, a simple impairment test can be completed. This has been successful in jurisdictions around the world. It has even caught up to the technological age, and apps such as DRUID app takes the guesswork out of it. Why is it that the Australian governments want to hold on to archaic methods of testing for drug impairment. It seems odd to want to do so when the equipment is so expensive and road toll even more costly both financially and from a human perspective.

I myself am acutely aware of these facts. But the truth of the matter is that the law is changing as our society begins to understand how to better care for our people. This is apparent when you consider the doctors, scientists, and lawyers who prescribe medicinal cannabis and/or support changing these discriminatory laws.. What is not apparent in your letter or in the law is why the Road Commission remains incredibly hesitant to take the step forward not only to assist in public health and putting an end to discrimination, but also into ways that have already proven capable of making our roads safer.

We are calling on your department and other governmental organisations and those in Parliament to research the facts. This is integral to the protection and progression of Australian medicine. This is about public safety and the knowledge of the facts to help improve public health and safety.

I trust this has given you some facts you may not otherwise have known.

The Drive Change team and more importantly patients who desperately need your assistance will await your response on this matter.

Yours sincerely,

David HeilpernDirector of Change

Drive Change

The original letter sent to Drive Change can be found here.

The letter above is a slightly edited copy (due to the different medium) of this letter.